Years ago, while experiencing a particularly tough flare-up of my rheumatoid arthritis, I remember really struggling to worship. It was a season of increased pain (physical and emotional), frustration, and decreased quality of life. I felt like there was a … wall … between me and God, of hurt, confusion, and lack of understanding.

I didn’t doubt who he was, that he was in control, or that he loved me; but I didn’t understand what his purpose was in allowing me to suffer. Why was my heavenly “daddy” not stepping in to bring healing and relief? I wanted to step outside of my hurt, forget my troubles, and sing; but whenever I tried, I felt pain hit my chest – somehow both sharp and hollow – and I could neither hold back the tears nor articulate the words of the worship song in full swing all around me.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I needed a safe space to lament—to cry out to God, expressing my grief, calling on him to intervene, and releasing my burdens into his hands—and a modern praise and worship chorus wasn’t it. In our effort to share the good news (and it is good) and bring others to Christ, we sometimes shy too far away from the sorrowful realities of living in an imperfect world.

In a recent SATS interview with Dr. June Dickie and Rev. Dr. Lissa Wray Beal, we’re reminded of the value of lament and that it has a place in the church.

What is biblical lament?

Biblical lament is when we bring our suffering, struggles, and sadness to God, crying out to him both as a means of expression and because we know he is the only one who can make things right.

Examples of biblical lament

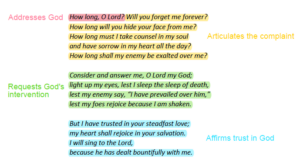

The Bible contains many examples of lament, including the majority of the Psalms, Jeremiah 11–20, 2 Samuel 1, Job, Joel, and when Jesus cried out to God on the cross (Matt 27:46). While lament comes in different forms (written, spoken, sung, or quiet prayer), all biblical lament shares a few key elements. As Rev. Dr. Wray Beal pointed out, it:

- Addresses God.

- Articulates the complaint.

a.Sometimes: Presents a reason for the affliction.

- Requests God’s intervention.

- Affirms trust in God.

a. Sometimes: Ends off with praise.

We can see these key elements in Psalm 13, for example (Psalm 13:1–6 ESV):

History of lament within the church

The obvious question that follows is: Well, why isn’t it more prominent in our churches today? Dr. June Dickie answered this when she outlined the following historical sequence of events:

1500s – Martin Luther believed lament to be a useful practice. John Calvin also encouraged believers to lament.

1700s – The practice of singing lament Psalms persisted.

1800s – Popular Protestant hymn writers moved away from singing laments. The focus became hymns.

1980s – Leaders felt lament should be a private practice, and praise and worship choruses became more popular.

“Somewhere along the way, we modern Christians started to think of lament as optional instead of a required practice of faith,” added Dickie.

The importance of lament

The problem with neglecting this practice is that doing so leaves the church less equipped to support and meet the needs of people who are suffering. If we only present the joyful part of our relationship with God, we not only misrepresent our faith but also alienate those who are not walking through a joyful season.

As Dickie put it, quoting Scott Ellington, when our experience of God doesn’t match what we believe about God, we have two ways to respond:

- Walk away because God “doesn’t work”.

- Engage with God, pouring out our hearts to him and asking him what’s going on—lament.

Option 1 turns away from him; Option 2 turns towards him and deepens our relationship with him. That is the importance and value of lament: It is part of an authentic and lasting relationship with God. To bring our pain, anger, and questions to God and trust that he won’t turn away from us is a heroic act of faith.

Lament at a congregational level also allows us to intercede for our brothers and sisters who are suffering—to stand in the gap for them—and to demonstrate our love for them through listening to, accepting, and supporting them right where they are, in the thick of their pain.

How does the church recapture this powerful part of our relationship with God?

The first step is to recognize that lament is an acceptable—required, even—part of practicing our faith. Including biblical lament in our readings and teachings will help to open the door to this practice for those who have no knowledge of it. Dr. Dickie recommends starting with a simple example like Psalm 3 or Psalm 13. Dr. Wray Beal spoke about giving pain-sufferers an opportunity to write a lament of their own, based on the structure of a biblical lament.

Then, instead of hiding it away in a private, back-room space only, we need to give believers opportunities to lament when we gather; instead of expecting those walking through painful seasons to hold back their tears, we need to make sure they know they aren’t alone and that it is okay to cry out to God in the midst of suffering.

It wouldn’t be accurate to say my painful season caused me to turn away from God; but it was a time of distance between us. I am thankful that he never gave up on me and with time and a few hard lessons, brought me back into a deeper, more meaningful, and lasting relationship with him.

But what I wish for others is that that need for expression and the release of their burdens is well met within the context of a church family, right there at our Father’s feet.

- Watch “The Value of Lament for the Believer Today”, the SATS interview with Dr. June Dickie & Rev. Dr. Lissa Wray Beal on the SATS YouTube channel.

- Contact SATS to find out more about biblical lament.

- Read a related article on mourning women, called “Allowed to Feel.”

- Catherine Falconer’s “Deliver us!” may interest you too.

Short Bio: Carrie Milton is a veterinarian and language practitioner. After completing her Bachelor of Veterinary Science and working with a variety of animals for a number of years, she reawakened her love for the written word. Accredited by the Professional Editors’ Guild, she has tried her hand at everything from theses to fiction.